What has surprised me about teaching only Middle School (G6, 7 and 8) at UWCSEA is how much harder it has been. At Grade 12 I had to think deeply about texts and how to connect students to the ideas but what I taught and what the students needed to be able to do was clearly defined - this part of the learning didn't require much thinking at all.

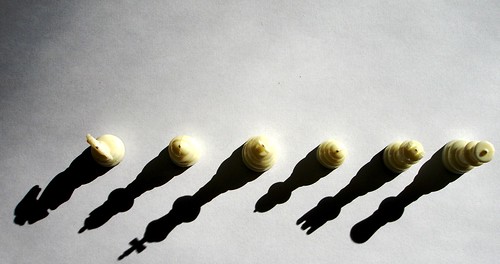

At Middle School we have to think not just about the "what" of our teaching, but also the "how" and the "why". Over the last 15 years, Middle Schools around the world have been going through a curriculum revolution and it occurs to me that only now are the many pieces of the new understandings about what it means to teach young adolescents coming together. We began with research into the unique developmental needs of adolescents. Concurrently curricula authorities began looking at benchmarking and sequencing K to 10 curricula. As these two pieces come together, Middle School teachers find ourselves at the pointy edge of a new set of curriculum understandings. Grade 12 students have a skill-set not too far from my own; thinking my way through how a Grade 7 student might best grasp an idea takes considerable imagination and energy.

I articulated some of these ideas this week in response to a question from a parent about why we don't do more essay writing in Middle School. Here's what I wrote:

As you may know, UWCSEA made the decision a few years ago to review our curriculum and develop Standards and Benchmarks for a unique UWCSEA curriculum. What we found as we compared English curricula from around the world and looked at our own teaching practice, was that, from Primary to IB, we were doing a good job of teaching students many of the writing skills associated with essays but that we needed more emphasis on the thinking skills. The students who are most successful with essay writing in Grade 12 and University are those who see the form as a media for thought and have the confidence to adapt and build their writing to match their own insights and the needs of their audience.Writing a good essay is about a lot more than putting pen to paper. If students are to do this writing part well, they need some complex reading and thinking skills so that they have something meaningful and engaging to say. We know from the research into how Middle School students learn, that this is an important time for building student's thinking skills and autonomy. Students want to think for themselves but we also have to teach them how to support their ideas and arguments and how to engage critically and respectfully with the wider cultural world.What our review of the curriculum has shown us is that students need this greater emphasis on critical reading and developing the confidence and autonomy to make claims about the underlying ideas in texts; equally important is the close attention to detail to find appropriate supporting evidence for the things they want to say. When students are able to do these things - and they have been doing a lot of them in G6, 7 and 8 - they are doing the very important "pre-writing" component of the essay writing process. As adults, we sometimes form the misconception that having an opinion about a text (or about a topic in Humanities or Science) is a relatively easy process. Reading deeply, independently and widely and finding meaningful and appropriate evidence to support your arguments is a difficult skill that requires significant time and effort to learn.Which isn't to say that the writing component of an essay isn't also important. Knowing how to craft your words to say what you want to say clearly and appropriately is also a skill that needs to be taught and practiced. We do this mostly in smaller pieces of writing in the Middle School and often focus on forms other than essay writing recognising that students will have less and less space in the curriculum ahead to develop their capacity for creative writing and for writing in forms other than the essay, but that the best writers are those who can paint from a wide palette of skills.The writing mechanics for producing an essay are not, of themselves, terribly difficult but if we focus on them too early, students write essays that are hollow and dispiriting. If we can prepare our Middle School students to be careful thinkers who are learning to experiment and craft language, then our High School colleagues have the foundations they need to build strong academic writers in the final years.

As I sit here working on the next unit to teach my Grade 6 students, it occurs to me that it is no wonder it takes so much time and seems like such hard work. At UWCSEA we've articulated a clear and thoughtful description of what we think needs to be taught from K to 10. Translating these understandings into meaningful units which really prepare students well for each next step requires creativity, imagination and lots of time.

I miss the relative simplicity of Grade 12 but I'm relishing the challenge of Middle School.