Writing curriculum is a adventure story all of its own.

|

| By Alfred Henry Miles (1848-1929) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

I wrote in November about the power of seeing curriculum as dialectical rather than as a linear narrative. In essence, the argument was that student learning is more effective when curriculum content* is constructed through an ongoing conversation between teachers and the curriculum authority rather than being mandated by a set of commandments from on high. The agency this gives teachers translates into agency for students. When curriculum is based on an understanding that 'the mystery of discourse is not order, but disorder, incoherence, the possibility of the unthinkable,' to quote the sociologist Basil Bernstein (Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity p. 11), then teaching and learning can be truly empowering; students can be prepared for a world where they have the agency to change the defining discourses rather than being controlled by them.

The power and potential of the approach that UWCSEA has taken through writing its own curriculum was highlighted for me this week both in my classroom and in the weekly planning session with the Grade 8 English team.

Let me tell the story...

...o0o...

Making sense of the world

A play in one act

SCENE: Jabiz's classroom. A classroom on the 5th floor of UWCSEA's East campus in Singapore. The structure of the room is quite traditional but Jabiz has brought it to life with pot-plants and cushions and clear demarcations between the working spaces (chairs and tables around the back of the room) and the instruction space (couches and beanbags at the front of the room). Sitting on the couches looking at the whiteboard are Jabiz, Stuart and Ian. The two other members of the team, Paula and Adrienne, are in Manila and Phnom Phen respectively. Paula is helping to select the next group of Scholars to represent the Philippines at one of the 14 United World Colleges around the world. Adrienne is in Cambodia on a service trip using her ICT skills to help support learning in a range of schools that UWCSEA work with. (The location of Paula and Adrienne is not directly relevant to this story but it is pretty cool! - it shows how serious the school is about its mission to use education to make a better world). On the whiteboard is a projection of the planning document for the current Grade 8 unit on reading.**

JABIZ: Hey, I'm really liking the way the kids are getting into this unit at the moment.

IAN: Yeah, one of my kids greeted me in class today by saying "can we learn like this all the time?"

STUART: Agreed. We talked a few weeks ago about how the students seemed less motivated than we wanted but they have definitely turned a corner. What are we doing right?

JABIZ: I think it's down to the choices we're giving them. Modelling the skills first and then getting the kids to demonstrate their understanding in novels that they choose is the way to go.

IAN: Choosing the right books is key here though...

JABIZ: Exactly. So we model by working through a common class novel that is a bit easier and accessible and then we put the kids in groups to try out the skills on books that are right for them.

IAN: I think that's the thing we really nailed in this part of the unit: putting the right groups of kids in front of the right novels.

STUART: Agreed. That's where our professional judgment based on our knowledge of the students comes into play. So how are they getting on with the skills?

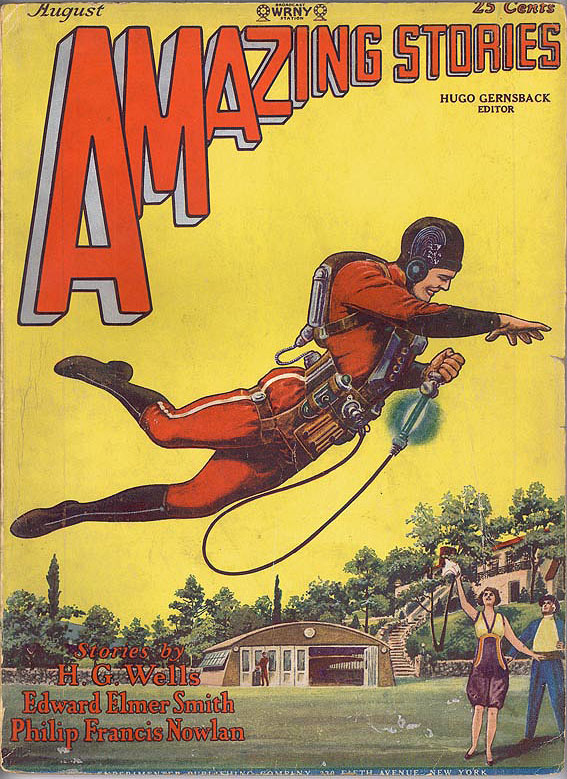

|

| Frank R. Paul [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons |

(Our 3 adventures look towards the the Planning document projected onto the screen in front of them. Jabiz clicks the link to the POE for the unit and the key skills are highlighted as follows:

I can identify alternative interpretations of a text.

|

I can consider and use others' interpretation of a text to deepen or alter my own.

|

I can identify how an author has constructed a narrative point of view.

|

I can explain the impact of a narrative point of view on my interpretation.

|

I can identify examples and explain how the author creates voice through diction and literary techniques.

|

I can explain how the author's use of voice in the text has shaped my interpretation of the text.

|

JABIZ: Yeah, it all seems to be coming together. They're making the transfer from the class texts like I said.

IAN: I agree, but there's something bugging me. These skills all come from our Reading Standard and they all focus on craft skills that a writer uses when they construct a text. I think they're important but they're only part of the story.

JABIZ: (in a supportive and thoughtful tone - without nearly the level of exasperated condescension that might be expected towards a colleague who questions everything and uses conversation to sort out his ideas rather than taking the time to do it in the privacy of his own blog). This is what you were talking about yesterday when you were going on about the lack of Benchmarks to articulate the purpose of reading.

IAN: (oblivious) Yeah. This is part of the struggle I've had to explain the transition between "learning to read" in Primary School and "reading to learn" in High School. We're right in the middle of this process in Middle School and something hit me about the way our current unit is working.

STUART: Go on.

IAN: Well, all our Benchmarks at the moment are about craft - I know this isn't strictly accurate, but the emphasis is very much on how a writer writes. But that's not why I read books nor why I think writers write them. They write because they have something to say about the world and I read because I want to know what it is. How they write is interesting and important but it's not the main game. I don't think we teach English in High School primarily because we want students to know how to read and write but because we want students to use these understandings to engage with the cultural understandings that writers share.

STUART: You're right. This idea is stated clearly in all the position statements for English Curricula that we looked at when we started work on our curriculum but it seems to get lost when you get to the fine detail. All around the world English Curricula say things about focussing the ethical and social understandings of writers, but they struggle to articulate what this looks like when it comes to the specifics of what to teach in the classroom.

JABIZ: So is that our Standard "Humans use story to make sense of the world?"

STUART: Yes, I think it is.

IAN: Interesting that we articulated all our Standards around craft and that we haven't worked out what the details of our Standards around content are yet. There's something going on here about the way we think as a profession and as a culture about learning - what can be taught and measured etc. We go for the more easily measurable first.

STUART: Looks like the time is right to articulate this next Standard. I'll set up a meeting.

NARRATOR: And so the curtain falls on yet another curriculum adventure and our protagonists return to their classrooms a little wiser and with yet another meeting to attend.

The End

...o0o...

Humans use story to make sense of the world

Interestingly, when I went just now to look at the Australian Curriculum, there are Level Descriptors under the Literature Strand that say something about the content as opposed to the craft of writing but they are very much in the minority. Of the 10 Level descriptors for Grade 10, here are the two which I think are not primarily about craft:

Compare and evaluate a range of representations of individuals and groups in different historical, social and cultural contexts.

Evaluate the social, moral and ethical positions represented in textsAnd I wonder to what extent these Descriptors are engaging with the idea of story. Writers make a deliberate decision to write narrative rather than philosophy, for example. There is something in the nature of the narrative mode that represents an ordering of the world which is in contrast to a philosophic or analytical approach. I'm reminded of the line attributed to Novalis that 'poetry heals the wounds inflicted by reason.' My best students have always been those who can dance poetically with the texts they analyse.

I'm not sure what our articulation of "the world as story" will look like or even if it makes sense to "analyse" something which is assumed to be outside of "reason". What I love is that we have a process for trying and that I get to share in this adventure.

And I can't help wondering if we might be trying to articulate the wrong Standard. Perhaps the point isn't to make sense of the world but rather to enjoy it: it might be the playfulness that enters these stories that we make together - in our meetings and in our classrooms - that really matters. We spend so much time applying the scalpel of reason to our world and rewarding those who can cut with the most precision; perhaps what we need is a way to value those who heal with humour and playful subversion.

How on earth could we write an assessment criteria for "constructive subversion"?

*My argument is based on my areas of expertise in the liberal arts and specifically "subject English". Basil Bernstein in Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity argues that pedagogic practice is systematic across schools and, indeed, 'is a fundamental social context through which cultural reproduction-production takes place' (p. 3). According to Bernstein's formulation of cultural reproduction, the argument should be equally valid across the school curriculum but I don't feel that I have the expertise to speak other than tentatively about the experience of teaching and learning in other areas of the curriculum.

** Apologies to Stuart and Jabiz whose dialogue is in the spirit of our conversation but in no way accurate.